Nuclear’s role in the hydrogen economy

Hydrogen is rapidly moving to the center of Europe’s decarbonization strategy. It is seen as the missing piece for decarbonizing “hard-to-abate” sectors such as steel, cement, fertilizer, refining, and heavy transport. The European Commission’s Hydrogen Strategy envisions 40 GW of electrolysis capacity by 2030 and a mature market by 2050. Despite its promise, the hydrogen economy remains overwhelmingly fossil-based: more than 95% of hydrogen is produced via natural gas reforming, which emits approximately 830 million tonnes of CO₂ annually.

If hydrogen is to contribute meaningfully to climate targets, it must be produced at scale, with low or zero emissions, and at costs competitive enough to replace fossil-derived hydrogen. Renewables paired with electrolysis are central to current roadmaps, but they face systemic challenges: intermittency, land-use pressures, and the massive overcapacity required to deliver consistent hydrogen output. This is where nuclear enters the equation. With its ability to provide constant, large-scale, low-carbon electricity and heat, nuclear is uniquely positioned to anchor the hydrogen economy.

The question is no longer whether nuclear can produce hydrogen; it already does at pilot-scale. The challenge is whether nuclear can become a backbone of hydrogen supply chains and how financing, infrastructure, and policy must evolve to unlock that potential.

Comparative economics: nuclear hydrogen vs. renewables + electrolysis

The economics of clean hydrogen depend on three factors: electricity price, electrolyzer efficiency, and utilization rate. Renewable-powered electrolysis can achieve low electricity costs during peak production, but intermittency results in low capacity factors—often below 40%. This dramatically increases the levelized cost of hydrogen, since electrolyzers must be oversized or paired with costly storage to ensure stable output.

By contrast, nuclear power plants operate with capacity factors above 90%, providing constant electricity and heat. When coupled with electrolysis, nuclear can maximize utilization rates, lowering the per-unit cost of hydrogen. According to the OECD-NEA, nuclear-powered electrolysis could achieve costs of $2–3/kg of hydrogen by 2030, particularly when combined with high-temperature electrolysis, compared to current renewable-driven averages of $4–6/kg.

This difference is strategic. In heavy industry, where hydrogen is not just an energy carrier but a raw material, cost competitiveness determines adoption. If nuclear can deliver steady, affordable supply, it has the potential to complement renewables and accelerate hydrogen’s penetration into core industrial processes.

Strategic projects: from France to Eastern Europe to the Gulf

Momentum is building globally around nuclear-hydrogen integration.

- France is leveraging its strong nuclear fleet to explore nuclear electrolysis. EDF and partners are studying the potential of coupling existing reactors with electrolyzers to produce low-carbon hydrogen for refineries, fertilizers, and mobility. This aligns with France’s hydrogen roadmap, which sees hydrogen as critical to achieving net-zero while preserving industrial competitiveness.

- Eastern Europe is emerging as a testbed for nuclear-hydrogen synergies. Poland, Romania, and Czechia—all heavily reliant on coal—are evaluating SMR projects that could simultaneously decarbonize power grids and supply hydrogen for industry. Romania’s Nuclearelectrica has explicitly positioned SMRs as dual-purpose assets for electricity and hydrogen production.

- The Middle East views hydrogen as both a tool for decarbonization and an export commodity. The UAE, already operating the Barakah nuclear plant, is assessing nuclear-powered hydrogen production as part of its diversification strategy. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 includes ambitions for large-scale hydrogen exports, with nuclear offering a pathway to scale production beyond renewables in desert environments.

- The U.S. and Canada are investing heavily in demonstration. The U.S. Department of Energy is funding projects coupling existing reactors with electrolysis, including at the Palo Verde and Nine Mile Point plants. Canada’s CANDU refurbishment program is being linked to future hydrogen production opportunities.

These projects suggest a shift: nuclear is no longer seen only as a baseload electricity provider but as a multi-purpose industrial energy hub.

Advanced reactors: unlocking efficiency for hydrogen

Current light-water reactors can power electrolysis, but advanced reactors bring an even more compelling proposition. High-temperature gas-cooled reactors, sodium-cooled fast reactors, and some SMR designs can deliver process heat at 700–900°C, which is precisely in the range required for high-temperature electrolysis or thermochemical cycles such as the sulfur–iodine process.

By using both electricity and heat, advanced reactors can achieve hydrogen production efficiencies far above today’s systems. The IAEA notes that these approaches could reduce hydrogen costs by up to 30–40% compared with conventional electrolysis powered by electricity alone. Demonstration efforts in Japan, with the HTTR project, China with the HTR-PM project, and the U.S. show that advanced nuclear-hydrogen coupling is not just theoretical but increasingly practical.

This technological shift positions nuclear not just as a power generator, but as a cornerstone of integrated industrial decarbonization.

Synergies with district heating and industrial clusters

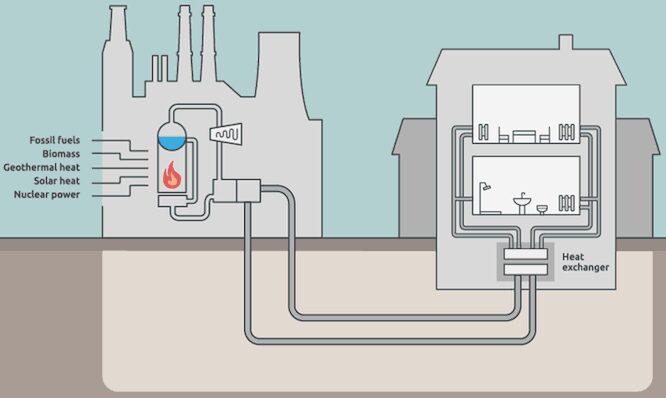

The strategic value of nuclear hydrogen is amplified when considered alongside other applications. Nuclear plants co-located with district heating networks can simultaneously provide heat to urban centers, hydrogen for industry, and electricity to the grid. This multi-vector approach maximizes asset utilization and strengthens the economic case for investment.

Industrial clusters represent another critical synergy. Steelmaking, cement, and chemical industries require both hydrogen and high-grade heat. Locating nuclear hydrogen projects within or near these clusters reduces transport costs, ensures steady offtake, and enhances competitiveness. Europe’s concept of hydrogen valleys, integrated ecosystems where production, distribution, and use are co-located, could benefit significantly from nuclear, which provides the steady base that renewables alone cannot guarantee.

This integration transforms nuclear from a sectoral solution into a systemic enabler, embedding it into broader industrial strategies.

Policy and investment frameworks: the missing link

Despite the technical potential, nuclear’s role in the hydrogen economy remains underdeveloped in policy frameworks. Most national hydrogen roadmaps focus heavily on renewables, with nuclear often absent from funding and certification schemes. This lack of explicit recognition creates uncertainty for investors and limits the scale of projects.

Momentum is shifting slowly. The OECD-NEA has called for greater integration of nuclear into hydrogen strategies, stressing that energy security and climate goals cannot be achieved without it. The IAEA continues to emphasize nuclear’s role in non-electric applications, including hydrogen.

From an investment perspective, hydrogen projects are capital-intensive and face long lead times. They require patient capital and risk-sharing mechanisms. Instruments such as contracts for difference, green hydrogen certification schemes that include nuclear, and public-private partnerships will be decisive. Investors will also demand robust offtake agreements from industries such as steel and chemicals to de-risk demand.

Without these frameworks, nuclear hydrogen risks remaining at the demonstration stage. With them, it could scale rapidly, anchoring the industrial hydrogen economy.

Hydrogen will be indispensable to Europe’s and the world’s decarbonization pathways. But the idea that renewables alone can supply the hydrogen economy is increasingly being challenged by realities of scale, intermittency, and cost. Nuclear provides the stability, efficiency, and industrial integration needed to turn hydrogen from a niche technology into a backbone of industrial transformation.

The question is not whether nuclear can produce hydrogen—it already can. The real question is whether governments, investors, and industries will align the financing, infrastructure, and policy frameworks necessary to make it competitive at scale.

If they do, nuclear will evolve beyond its traditional role of powering homes and cities. It will become a cornerstone of industrial decarbonization—producing hydrogen for steel, heat for communities, and resilience for economies. In short, nuclear could be the enabler that turns hydrogen from aspiration into reality.

The end of the Hydrogen hype, a new opportunity for pink Hydrogen?

Although hydrogen has a lot of potential for decarbonization and heavy investments have been poured into this industry, many projects have been canceled. As of December 2025, more than 60 major hydrogen projects have been canceled.

One of the key reasons is the long adoption process from end users as they do not want to pay a premium price. With only 7% of hydrogen projects having successfully passed the FID – in comparison to higher pass rate in more mature industries, it shows there is still work to reduce prices, secure investors and end users.

This is where nuclear power could play a key part. Retrofitting existing plants, would allow at a reduced CAPEX to produce pink hydrogen while advanced nuclear with its already embedded cogeneration could deliver the molecule from day 1.

Although, we have been talking about the end of the hydrogen bubble for years, now is the time for hydrogen projects, with more mature approaches and a cost spending-discipline, relevant projects for end users will be able to bring their promises.